1762 - 1763: Princeton and beyond

This section looks at the authenticity of several compositions that have been attributed to Lyon from 1762 and 1763, and the development of the commencement entertainments in Princeton and Philadelphia in the 1760s.

Three years after finishing his A.B. Lyon was back in Princeton to receive his master’s degree. He would only be in New Jersey for a two or three more years before moving north to Nova Scotia to begin his Presbyterian ministry there in 1765. His ordination in 1764 by the Synod of New Brunswick seems to have been the effective end of his musical career. Gilbert Chase, in his mid-twentieth century history of American music identified only four compositions by Lyon that survive from after his ordination, the most popular being an “Ode on Friendship” that first appears in John Stickney’s Gentlemans’ and Ladies’ Musical Companion in 1774. Despite this limited output, Lyon’s enthusiasm and talent for music was still known to his friends. Fellow Princeton graduate Philip Vickers Fithian recalls fondly his afternoon singing with Lyon in New Jersey in 1774:

April 23. At home drawing off some of Mr Lyons Tunes, & revising my own Exercises—The morning pleasant but the weather dry. Afternoon according to appointment I visited Mr Lyon at Mr Hunters. He sings with great accuracy. I sung with him many of his Tunes & had much Conversation on music, he is vastly fond of music & musical genius’s We spent the Evening with great sattisfaction to me.

Not wanting to disappoint his friend, Fithian made sure that he practised before meeting Lyon. Certainly if they were performing any of Lyon’s compositions, Fithian would have been a very competent singer.

Lyon would also have needed very capable voices for the music he wrote in 1762. For this commencement ceremony he composed not one but four choruses as part of a dramatic “entertainment” performed by the candidates for the Bachelor’s degree. This entertainment was subsequently published by William Bradford of Philadelphia, but without attribution of either the poet or the composer. Once again, Lyon’s authorship is not entirely clear. Perhaps these choruses are by Joseph Periam who had so diligently kept a commonplace book of music? Oscar Sonneck believed that these pieces were indeed by Lyon, and many have taken his word for it. In this final section I want to explore the question of authenticity and the emerging genre of college commencement entertainments at the College of New Jersey and College of Philadelphia, looking particularly at “The Military Glories of Great Britain” (1762) and “An Dialogue on Peace” (1763) both performed in Princeton.

“The Military Glory of Great Britain” (1762)

From 1761, and the quasi-operatic commencement music composed by Francis Hopkinson, the closing entertainments at the Colleges in Princeton and Philadelphia started to go beyond standalone musical performances. They became political dramas with several actors and a series of musical interludes, primarily in the form of choruses. With “The Military Glory of Great Britain” in 1762 the political message, on the face of it, is clear. After an opening chorus proclaiming the power and glory of Great Britain the speakers enter in turn to give a poetic narrative of recent military victories. For the most part it is overblown imperialistic bombast; though, perhaps this is unsurprising given that French and Indian War was essentially over, with Great Britain as the clear victors. Perhaps more significantly the new Colonial Governor of New Jersey, Josiah Hardy, was in attendance as the previous Governor had been in 1760.

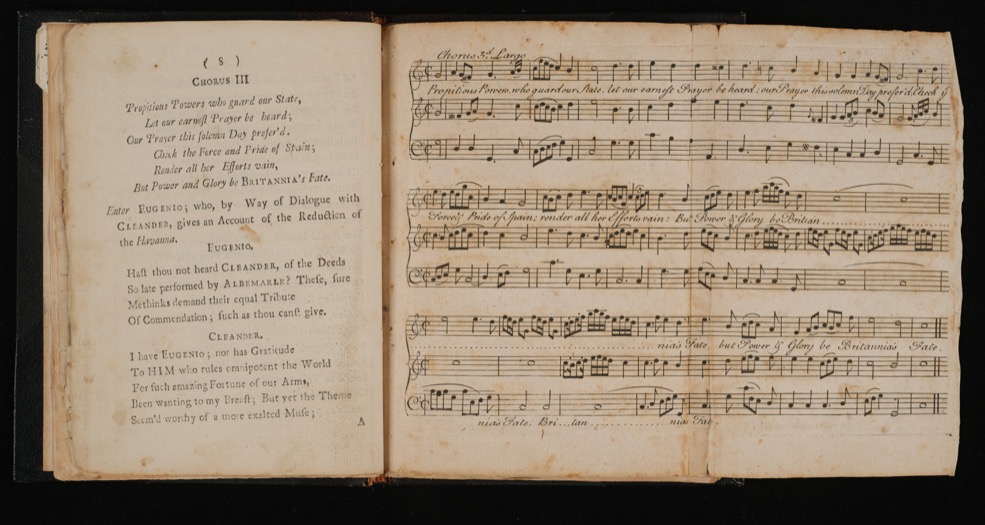

The four choruses that accompany this entertainment match the martial and celebratory nature of the text. Each chorus is written on three staves with the melody in the top stave and there is also clear indication of an instrumental accompaniment (most likely played on the organ discussed in 1759-1760: Beginnings). If any women were singing, they would have doubled the melody at the octave creating a four-voice texture (Ogasapian 2007, 24). This seems unlikely, however, since we know from newspaper reports and its subsequent publication that it was performed by the graduating A.B. candidates. But the real question for us is whether or not this is by Lyon. Without corroborated documentary evidence will never know for sure; however, by looking at the verified surviving compositions by Lyon we can identify some “fingerprints” of his musical style.

These fingerprints are particularly noticeable as most are considered faults in traditional counterpoint. (Lyon would have struggled with the current music theory courses at Princeton.) Looking particularly at his two pieces in Urania and the later “Ode to Friendship,” these errors become a recurring pattern. These faults include parallel movements in octaves and fifths, incomplete triads, inconsistent harmonic rhythm, mostly root position triads and chord progressions, irregular and unbalanced phrase lengths, the list could go on. These features, however frequent they might be in Lyon’s music, are hardly surprising given the lack of formal theoretical training available at the time. Instead, what strikes me as particularly Lyon-esque is his sudden use of raised 4ths (giving the impression of a secondary dominant) without ever modulating to a different key. Another distinctive feature is his use of the same cadential formula to end nearly every piece, involving a halving of speed, and a [V6/4 - 5/3 – I] progression with the melody falling from the third degree of the scale by step to the first.

Returning to the choruses of “The Military Glory” having identified these musical fingerprints, the possibility of Lyon’s authorship becomes far more probable. The third chorus, “Propitious Power,” is, for example, riddled with unmodulating secondary dominants. As with all four pieces in 1762, this chorus ends with the same cadential voicing that Lyon almost always uses, half also have his characteristic halving of speed into half-notes. I would like to stress, however, that this type of brief and limited analysis only serves to address the possibility of Lyon’s authorship. It is not in any sense proof. But until evidence to the contrary appears, we can tentatively attribute this music to Lyon so long as we also acknowledge that it is not fully verified.

“A Dialogue on Peace” (1763)

While some scholars have pointed to Lyon’s probable authorship of the music in “The Military Glory,” very few have included the 1763 commencement entertainment “A Dialogue on Peace” in biographies or discussions of the composer. (One exception is Stephen L. Pinel in Old Organs of Princeton, 1989.) This seems rather strange to me given that of the six pieces of music in this publication, four have exactly the same music as the 1762 entertainment. In other words, all four compositions from “The Military Glory” were performed a year later but with new words. At the time of writing I have not found any mention of this in the literature on Lyon and early American music. The text of the Dialogue is an original work attributed to the poet Nathaniel Evans, and is not as bellicose as the commencement entertainment the year before. Most of the music is is sung at the end of the entertainment, unlike in “The Military Glory” that interspersed choruses into the drama.

It is not so much the repetition of the previous year’s music that is surprising here, but rather the inclusion of two new pieces. Is there any possibility that these are by Lyon? I do not think that the reuse of the 1762 choruses is an indication of Lyon’s authorship. Looking, for example, at the published editions of the commencement entertainments at the College of Pennsylvania in 1766 and 1767, where the “Duet” and “Air” of both years were probably set to the same music, students in this decade had few qualms about writing new texts to existing tunes. We should look instead at the features of the two new pieces of 1763. And there are some striking differences to what the previous year’s graduates had heard. The opening solo and chorus is far more ambitious than any of the 1762 choruses. Instead of being just one repeated chorus, this piece has a number of sections including an extended instrumental introduction, a combination of solo and choral sections, and a section in different key: these are features that we do not find in 1762. In general the vocal writing is far more polished, with relatively few obvious contrapuntal errors, and a far more regular phrase and harmonic rhythm. The cadences are far more varied, and the use of secondary dominants is more carefully managed. Unlike the choruses of 1762, I am very hesitant to suggest that this is by Lyon.

The other new 1763 composition would also be atypical if it were by Lyon. It has a compound time signature unlike pretty much anything else he wrote, and is written in a flat key (F major), which is similarly unusual. It would be easy at this point to assume that piece is also by a different anonymous composer, however there are still some of Lyon’s fingerprints. The cadences are particularly typical of Lyon, as is the prevalence of root position triads and irregular phrase lengths. Lyon’s involvement in this 1763 music is somewhat of a mystery. In fact we have no reason to believe that he had anything to do with this commencement despite being in the area. But then who else could have written this music? Maybe there are more musically literate students at the College in the 1760s that we think. Perhaps the anonymous composer (or composers) was inspired by Lyon’s published work. For now I will have to leave these questions unanswered.

Legacy in Princeton and beyond

I have not been able to find another published commencement entertainment from Princeton in the 1760s after “A Dialogue on Peace”, whereas there are almost yearly issues of the Dialogues and Odes performed at the College of Philadelphia. It is perhaps no surprise that there is neither mention of music nor a publication of the commencement entertainment in 1765, for example, given the implementation of the widely unpopular Stamp Act of 1765; nothing would have been more inappropriate than singing the glories of Great Britain. The 14th October edition of the New-York Mercury rather touchingly commented on the patriotic nature of this commencement event at the College of New Jersey in 1765. After describing the orations on frugality and liberty, the reporter describes the boycott of British clothing by the students:

To testify their zeal to promote frugality and industry (so warmly recommended in several of their performances) they unanimously agreed, sometime before the commencement, to appear on that public occasion dressed in American manufactures, which very laudable resolution they all executed, excepting four or five, whose failure was entirely owing to dissapointments, though we doubt not but they made a much more decent appearance in the eyes of every patriot present, than if the richest production of Europe or Asia had been employed to adorn them to the best advantage.

These commencement celebrations were more than ceremonies to administer degrees: they were very public displays of national sentiment. During the course of the 1760s and into the 1770s there is a clear change in the subject matter of commencement entertainments from exalting the British monarch to promoting freedom and liberty (Winstead 2013, 33). This can be seen particularly in the published entertainments from the College of Philadelphia. The combination of music and drama at colonial commencement ceremonies in the 1760s, far from being simply pleasant tributes to the graduating classes, was a reflection on the national identity of the colonies (Winstead 2013, 31). This practice as an artistic enterprise undoubtedly originates with Samuel Davies and James Lyon’s first commencement ode of 1759.

American music scholars have often pointed out that, in terms of musical style, Lyon (and Hopkinson) did not contribute to the development of a distinctly American sound (Temperley 1997, 21). It was not until William Billings (1746-1800) that America would get a composer whose music captured the spirit of early America and the very landscape it was sung in. This is perhaps because Lyon and Hopkinson looked to ape European styles—music that was written for courts and cathedrals—rather than developing a national, American music (Ogasapian 2004, 10). Lyon’s contribution to psalmody in America remains his greatest musical achievement; however, we should not downplay his contribution to the beginnings of a musical college tradition that now reveals so much about the changing political attitudes of a general public and the future leaders of the Patriot cause.