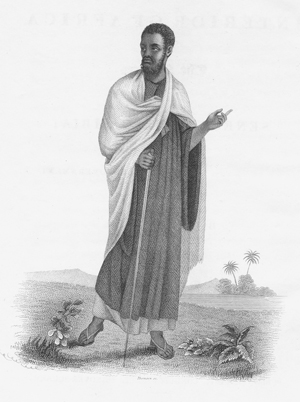

“Diai-Boukari”

A Marabout, named Diai Boukari, a native of the Foota country, was engaged as my interpreter and traveling companion, at a salary of one hundred and eighty francs per month. This man had been recommended to me for his attachment to Europeans, and for his integrity. He spoke the Arabic, Poola, and Joloff languages; his age was thirty-six years. . . . Before he embarked, my Marabout traced several Arabic characters on the sand, to ascertain if he should ever again see his wife and mother: the answer of fate being favourable, he put a handful of sand into a little bag, persuaded that on the preservation of this precious bag depended that of his life. [pp. 25-26]

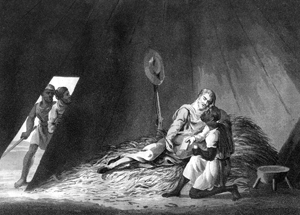

“The Author Taking Leave of His Friend at Diedde”

Having sent back our boats, we began to load our beasts, which was a business of some difficulty, owing to the darkness of the night. I gave my European clothes to my friend and put on the Moorish dress, but it did not sufficiently cover me, and I was soon assailed by a host of mosquitoes, which left me not a moment’s rest. My horse, tormented by these troublesome insects, ran off into the country: my Marabout pursued, and with much trouble overtook him. When all was ready I embraced my friend, whose tears betrayed his conviction that we were parting for ever. We separated, and I hurried my people after me . . . [Several days later] Unaccustomed as I was to travel in so hot a climate, and having every part of my body exposed by the Moorish dress to the scorching rays of the sun, I was reduced to such a deplorable state, that I began to think I had undertaken an enterprise beyond my strength. . . . The dress which I had adopted had not prevented me from being every where recognized as a European; I had therefore gained no advantage from it, and the Negroes beheld me with ill-will. The hatred which they bear against the Moors caused them to look with horror on one who had assumed their apparel. This being the case, I immediately dispatched Boukari’s slave to St. Louis, to request my friend to send me some European clothes. [pp. 27, 29-30]

"View of Canel, and Army of Foutatoro"

This little army presented an imposing appearance, for all the men of Foutatoro, when they go to war, wear a dress similar to that of the Mamelukes. All their white turbans and robes of the same colour, and the horses, which to the number of three hundred marched in two lines like our squadrons, produced a magnificent effect. Behind the cavalry marched the infantry, mostly armed with muskets. All these troops might amount to twelve hundred men. On approaching Canel they saluted Almany of Bondou with a volley of musketry. [pp. 135-136]

“View of the Sources of the Rio Grande, and of the Gambia”

April 12th [1818]. We had not been able to sleep quietly, for we were in constant alarm. In the morning, after making my guide eat a hearty breakfast to keep him in spirits, we pursued a western direction, taking bye-paths in the lofty mountains called Badet; we at length arrived at the summit of one of these heights; it was entirely bare, so that we could discover below us, two thickets, the one concealing from view the sources of the Gambia, (in Poula, Diman,) the other those of the Rio Grande, (in Poula, Comba.) The joy I felt at this sight could not be disturbed by the reflection of Ali, who the moment we perceived the two rivers said to me: “I fear they will murder thee, if they learn that thou art going to the sources; nevertheless, since thou wilt have it so, we will proceed towards them as if we were hunting, and Boukari on his side shall go to the neighbouring village.” The Poulas of Fouta Jallon call this village, the Sources. Satisfied with this arrangement, I however, prepared to resist any attack, and loaded my guns. [pp. 233-34]

“View of Timbo”

Timbo is situated at the foot of a high mountain. It contains about nine thousand persons, a spacious mosque and three forts, in one of which is the palace of Almamy, consisting of five large huts, regularly built. The fortifications are of earth, and falling to ruins; in several places they have loop-holes. Timbo must be a very ancient city; all the neighbouring country bears the same name. Hence sprung the present masters of Fouta Jallon, for the provinces comprised under that name have been conquered and were not originally subject to them. Timbo is the residence of the king and the army. I was informed that so many as a thousand horses are to be seen there. The inhabitants are rich. All the women have silver bracelets, and large gold ear-rings, and wear clothes of blue Guinea stuff, which is a sign of great luxury amongst these Africans. [p. 255-56]

“The Author at the Point of Death at Bandeia”

My situation actually grew worse; on the 8th of May a dysentery succeeded; I had no other remedy at hand, and no other food than a little rice and water. Such a diet soon exhausted my strength. On the 11th, after lying down on a bundle of straw, of which my Negro had made me a bed, I wrote my last will, under the impression that the next night would be my last. Boukari, seated by my side, supported my head to enable me to write; this faithful servant shed a torrent of tears, and when, after bidding him adieu, I put my journal and merchandize into his hands to be delivered to M. de Fleuriau: “Ah! my master,” cried he sobbing; “can I survive thee if Heaven should take thee away? No!”. . . . After giving directions for my funeral, for I was afraid lest the inhabitants of Bandeia, in the excess of their fanaticism might expose my body to the birds or to wild beasts, I fell into such a swoon, that I really thought I was going to sleep for ever; but a salutary crisis had taken place. On the 12th, when I awoke I was extremely surprised to find scarcely any thing the matter with me; the fever was gone, and I considered myself as nearly rid of the disorder. [pp. 271-72]

“Arrival of the Author at Bissao”

The large size of my Bambara hat, the thickness of my beard, the long stick with which I walked, the state of my clothes, which were almost all in rags, drew around me an innumerable crowd of Negroes, who incessantly insulted me, and laughed at my appearance. A Portuguese serjeant, seeing my embarrassment, drew his sword and restored order for some minutes; he then told me to follow him, and continued to keep off the multitude which obstructed the street leading to the fort. When I presented myself at the gate, the black sentinel, inferring the meanness of my condition from the bad state of my clothing, said to me in Portuguese: “Comrade, take off your hat.” Offended at receiving such an order, I looked at this Negro with a threatening air, and pulled my hat down further upon my head. I was immediately announced to M. de Mattos, the governor of the place, and appeared in the midst of a numerous circle of officers, who, hearing that a Frenchman had just arrived, ran to see me. . . . All eyes were fixed upon me; my dress appeared to some to be a disguise; they could not imagine that I belonged to a European nation. The governor enquired what motive had induced me to travel into the interior of Africa. . . . [pp. 325-26]