Francis Bacon, 1561–1626

Portrait of Francis Bacon. Frontispiece from his Francisci Baconi . . . Opera omnia quae extant, philosophica, moralia, politica, historica . . . (Frankfurt on Main: Impensis J. B. Schonwetteri, 1665) [Rare Books Division].

Called the father of empiricism, Sir Francis Bacon is credited with establishing and popularizing the “scientific method” of inquiry into natural phenomena. In stark contrast to deductive reasoning, which had dominated science since the days of Aristotle, Bacon introduced inductive methodology—testing and refining hypotheses by observing, measuring, and experimenting. An Aristotelian might logically deduce that water is necessary for life by arguing that its lack causes death. Aren’t deserts arid and lifeless? But that is really an educated guess, limited to the subjective experience of the observer and not based on any objective facts gathered about the observed. A Baconian would want to test the hypothesis by experimenting with water deprivation under different conditions, using various forms of life. The results of those experiments would lead to more exacting, and illuminating, conclusions about life’s dependency on water.

Throughout his life, Bacon lived mostly on the incline to success but beyond his means. He entered Trinity College at Cambridge at the age of twelve, traveled on the Continent, wrote significant and influential philosophical treatises and essays on reforming learning and reclassifying knowledge, served in Parliament, secured political appointments from Queen Elizabeth and King James I, was knighted in 1603, and became attorney general in 1613 and lord chancellor in 1618. However, always in debt, Bacon finally lost favor in 1621: he was convicted of corruption, heavily fined, and sentenced to the Tower of London (but was imprisoned only a few days). On a personal level, he was spurned for a wealthier man by the woman he loved, and he eventually married a fourteen-year-old when he was forty-five. Their marriage was fractious and soured, and he disinherited her in his will.

After the disgraceful end to his public life, Bacon devoted himself more fully to study and writing. Among his later works was a short piece of science fiction, New Atlantis: A Work Unfinished (published in Latin, 1624; posthumously in English, 1627), in which he envisioned a utopian society that embodied his aspirations for mankind. The setting is an island called Bensalem, discovered by a European ship that is lost in the Pacific west of Peru. The centerpiece of the model society is a state-sponsored college, “Salomon’s House,” instituted “for the Interpreting of Nature, and the Producing of Great and Marvelous Workes for the Benefit of Men.” Among its achievements are new foodstuffs and threads for apparel, artificial minerals and cements, accelerated germination of seeds, improved instruments of destruction (ideal societies are never safe), chambers where diseases are cured, and the creation of new and beneficial species. As one would expect in a Baconian world, there is a lot of experimentation conducted on the island and, more important, practical application of the knowledge gained. {For utopian maps, see the Utopia section of Theme Maps.]

Ironically, but perhaps not surprisingly, Bacon died from pneumonia while experimenting with snow as a way to preserve meat. His estate’s debts were substantial.

Bacon’s signature. From a letter from Bacon to “Mr. Auditor Sutton,” dated 14 July 1614 [Robert H. Taylor Collection, Manuscripts Division].

This copy contains only the second of the six parts of Bacon’s planned great intellectual “restoration,” the Novum organum, followed by a sketch of the third part. (Works that represent the first and third parts were published later; of the fourth and fifth parts only prefaces were written; the sixth was never begun.) The Novum organum, or “new instrument,” a reference to Organon, Aristotle’s work on logic, is Bacon’s most significant work, laying out his guidelines for interpreting nature. Unlike the ancients, who often contended that nothing can be known, he argues here that there are progressive stages of certainty, and he will show how through inductive reasoning they can be achieved.

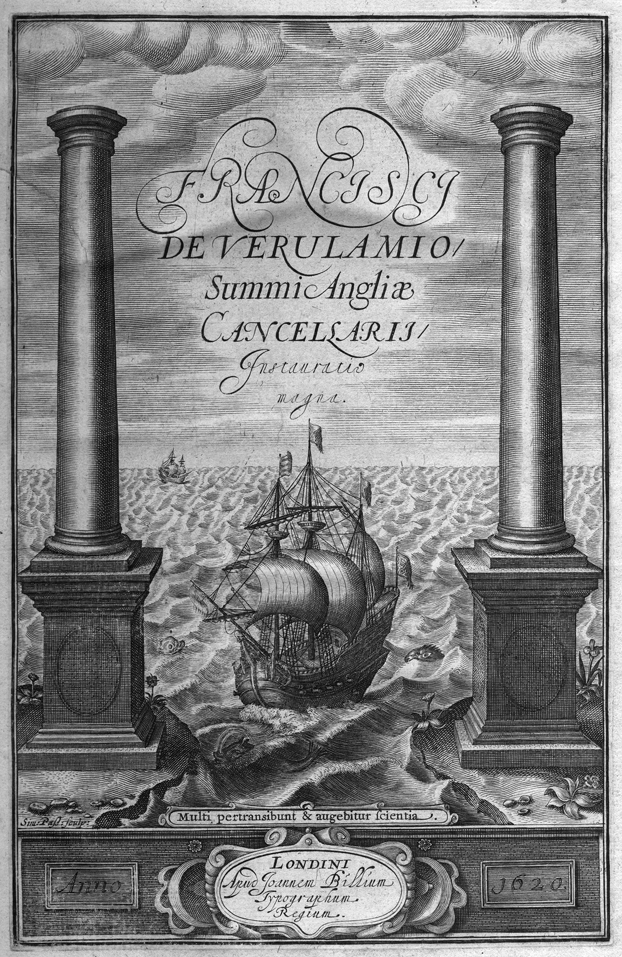

The title page exhibits a galleon exiting into the Atlantic Ocean from between the mythical Pillars of Hercules that stand on either side of the Strait of Gibraltar—hence, beyond the boundaries of the Mediterranean, or known world. The implications to the reader are clear: boldly embark on a voyage of discovery in which empirical investigation will lead to a greater understanding of the world. As the hopeful Latin caption states, “Many will pass through and scientific knowledge will increase.”

Departing for the New World from Spain in 1798 in a vessel not unlike the one pictured here, the German naturalist Alexander von Humboldt robustly would begin the realization of that dream.

Title page of Bacon’s Francisci de Verulamio, summi Angliae cancellarii, Instauratio magna (London: apud Joannem Billium, Typographum Regium, anno 1620) [Scheide Library].

“Aphorism I.” From Bacon’s Novum organum (1620).

Man, being the servant and interpreter of Nature, can do and understand so much and so much only as he has observed in fact or in thought about the order of Nature: beyond this he neither knows anything nor can do anything [p. 47].

The statement is the foundation of his scientific approach to acquiring knowledge. Later in the book, Bacon writes that printing, gunpowder, and the compass have revolutionized the world. But, of course, his scientific “method” (he never actually used that word) would have even more far-reaching effects. From our perspective today, what hasn’t it touched?Bacon’s thinking, applied to cartography, leads logically to thematic maps—particularly the quantitative variety—for they are visual hypotheses, either posed or proven, created from measurable, hence verifiable, data about the natural (physical and social) world.