Having thus endeavoured to state the different points of view in which the Cape of Good Hope may be considered of importance to the British nation, from materials faithfully collected, and of unquestionable authority, the result of the whole will, I think, bear me out in this conclusion:— . . . that, as a mere territorial possession, it is not, in its present state, and probably never could become by any regulations, a colony worthy of the consideration of Great Britain or any other power.

—Barrow, from his conclusion (Vol. 2)

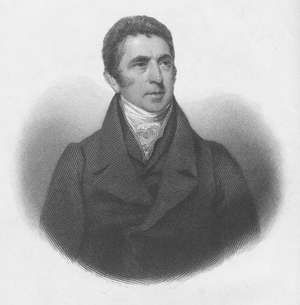

Barrow rose from common origins to become one of the most influential figures in British naval history. His first voyage was aboard a whaler to Greenland, which inspireda lifelong interest in the Arctic. His teaching skills in mathematics brought him into contact with Sir George Staunton, who recommended him to Lord Macartney for a staff position on a diplomatic mission to China. When Macartney was sent to Cape Town in 1797 as the first governor of Britain’s new colony, Barrow again accompanied him. He traveled extensively into the interior, assigned to reconcile disputes among the Boers, Hottentots, and Kaffers, who were striving to graze and hunt over the same territory, and to map the troubled area. (Not surprisingly, Barrow suggested that each group have it own exclusive area, an early form of apartheid.)

Utilizing the standard method of travel—a covered wagon pulled by a team of ten or twelve oxen—Barrow’s group made treks east across Karroo Land (arid desert) to the Graaf Reynett district, into the country of the Kaffers, then along the coast back to Cape Town. Next, they went north to the land of the Namaquas and circled back. Barrow’s personal equipment included a small pocket sextant, an artificial horizon (useful for determining latitude), a pocket compass, a small telescope, a case of mathematical instruments, and a rifle. His large, detailed map was further enhanced and improved a decade later by traveler William John Burchell [see BURCHELL].

In 1804, Barrow was appointed Second Secretary to the Admiralty, a position from which, over the next forty years, he effectively supported and encouraged British exploration, particularly in West Africa and the Arctic. “Barrow’s Boys” put the British stamp on vast areas of the unexplored world. He was also one of the founding members of the Royal Geographical Society in 1830.