Inside the Hellenic Collections: Post-Byzantine Greek manuscripts

Proskynētarion, 17th c. Guide to the sites of the Holy Land. Image of the kouvouklion (canopy) of the Holy Sepulchre.

Forty years ago, a gift from Stanley J. Seeger Jr. ’52 transformed Hellenic Studies at Princeton University. This series highlights the impact of Seeger’s gift on the collections of Princeton University Library and the research opportunities they afford.

Written by David Jenkins, Classics, Hellenic Studies, and Linguistics Librarian

The classification of Greek manuscripts often begins by distinguishing between those written before the fall of Constantinople in 1453, referred to as “Byzantine,” and those written after, or “Post-Byzantine.” While it is thanks to the generosity of two donors in particular, Robert Garrett and William Scheide, that Princeton University Library boasts one of North America’s largest collections of Byzantine manuscripts, the Stanley J. Seeger Hellenic Fund has partnered with the Library to acquire Post-Byzantine Greek manuscripts as well, a collection that now compliments and even rivals that of its predecessors.

The fall of Constantinople in 1453 to the Ottoman Turks meant that the production of Greek cultural artifacts now occurred within the context of Ottoman rule. While European printing begins precisely at this time and soon flourishes, the use of the printing press for book production in the Ottoman Empire was significantly hampered by both a ban that prohibited its use for works in Arabic and a clerical culture whose authority was based on an oral tradition carefully disseminated by manuscript.

Therefore, the printing of Greek texts occurred where it was more culturally and economically viable, within Greek-speaking European diasporas, primarily in Venice. While these European printers served the demand of a market large and accessible enough to justify the investment printing required, in areas under Ottoman rule Greek texts were still often copied by hand well into the 19th century in order to meet the needs of specific readers or communities.

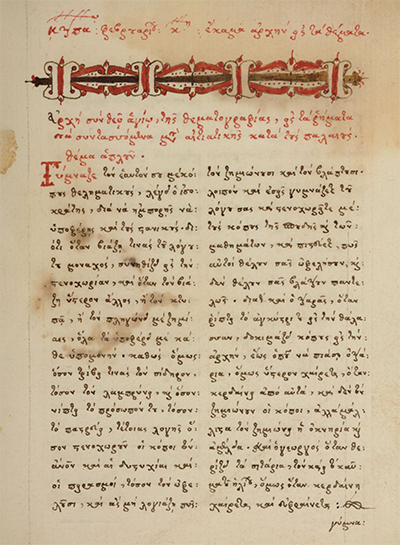

Hieratikon, 1679. The Service-Book of the Divine Liturgy of Saint John Chrysostom, Saint Basil the Great, and the Presanctified Gifts.

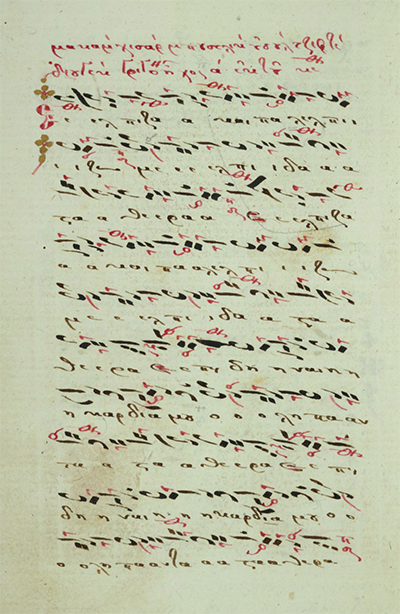

Stichoi tragikoi, circa 1820 (folio 10v). Hymns composed by Georgios Soutsos. Note the musical notion above each line of text.

As is the case among early printed Greek books for a Greek-speaking audience, liturgical texts are the most common among Post-Byzantine Greek manuscripts, in part because the musical notation used in these texts posed a significant problem for printers. Princeton’s collection includes many fine examples that document the development of Greek hymnody and its notation. These manuscripts also serve as physical compliments to the Kenneth Levy microfilm archive of medieval liturgical chant, which includes 250,000 manuscript pages of Christian liturgical texts from both the Eastern and Western traditions.

Another common type of Post-Byzantine manuscript is the Proskynētarion, or pilgrim’s guide to the holy sites of Palestine. These striking manuscripts often combine maps, text, and illustration and contain a wealth of information about the interests and sensibility of these early modern pilgrims.

Grammar Book, 1781.

Physikē / Johann Friedrich Wucherer, 19c. Translation from the German into Modern Greek by Eugenois Voulgaris.

Grammar books are also common and reflect both the educational aspirations and cultural identity of the Greek-speaking population under Ottoman rule. The text above on the left is an example of a “thematographia,” a textbook of exercises in Ancient Greek syntax. On the right is an example of an even higher level of education, a finely written manuscript of a German work on physics, translated into Greek by Eugenios Voulgaris, an important figure of the Greek Enlightenment of the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

![Medical receipts and commonplace book, [1617?]. f. 49v.](/sites/default/files/news/images/med%20recipts300cropped.png)

Medical receipts and commonplace book, (1617?). f. 49v.

Finally, “iatrosophia,” collections of folk remedies and treatments, are curious and valuable sources of information regarding the lives of the Greek-speaking population during this period.

In the middle of the page we find a recipe for hair growth, “Take cannabis root and boil it with pork fat. Apply it to the scalp and hair grows.”

For more information on Post-Byzantine Greek manuscripts, please see the informative blog post written by our former Curator of Manuscripts, Don Skemer.

Note: Hellenica features a sampling of the Hellenic Studies collections online.

Media contact: Barbara Valenza, Director of Library Communications

Newsletter

Subscribe to Princeton University Library’s e-newsletter for the latest updates on teaching and research support, collections, resources, and services.