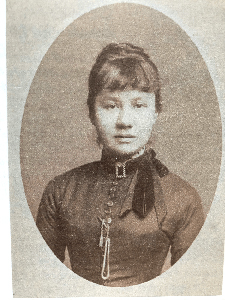

Johanna Van Gogh-Bonger (1862-1925): The unseen champion of Vincent Van Gogh

Photograph of Johanna van Gogh-Bonger, ca. 1884. F.W. Deutmann, Zwolle, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

The key role that Johanna (Jo) van Gogh-Bonger, his sister-in-law, played in championing the art of Vincent van Gogh was largely overlooked until recent decades. Following the rapid decline and death of her husband Theo only six months after the suicide of Vincent, the young widow made the decision to return to her native Holland with her infant son. Shortly after the death of Vincent, Theo had organized a memorial show of his brother’s work in the couple’s Montmartre apartment.

Crates of the artist’s paintings accompanied Jo back to Holland, against the advice of some of Theo’s former colleagues, who thought the ‘’difficult” work would be better served (and sold!) by established avant-garde art dealers in Paris. Johanna undertook the guardianship of the artist’s works and status very seriously – immediately reading and preserving the surviving correspondence between the brothers, in which Vincent grappled with descriptions of his torments and of his artistic process. She also pursued contacts with artists, critics, and intellectuals associated with the Dutch artistic journal De nieuwe gids (The New Guide) and beyond to better understand the artistic milieu and nascent social awareness from which Vincent’s singular genius emerged.

From Bussum, where she resettled and ran a guesthouse, she worked initially with the artists Jan Veth and Roland Holst to organize several Van Gogh exhibitions, including this one and other venues in 1892, and initiated several important European exhibitions in the following decades. Beginning in 1916, she spent almost three years in the United States trying to promote appreciation for his work in America – a challenging project at that time. She continued her careful curation of the artist’s works right up until her death in 1925.

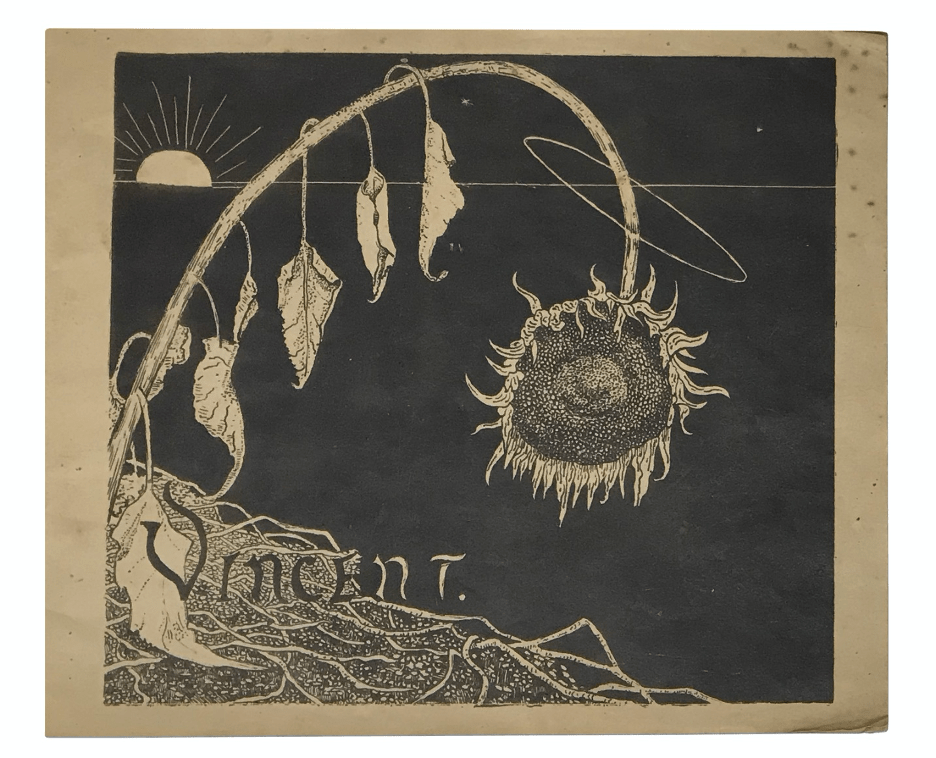

Cover of Tentoonstelling der Nagelaten Werken van Vincent van Gogh. Amsterdam (1892). Marquand Library of Art and Archaeology Tentoonstelling der nagelaten werken van Vincent van Gogh : December 1892. – Princeton University Library Catalog

Though her initial efforts to nurture the reception of Van Gogh were met with condescension by some of the male artists and critics she encountered – in addition to being female, she was trained neither as an art critic nor as business dealer – she became a powerful and astute guardian of and advocate for the artworks. Her example inspired her descendants to view the works remaining in family hands as national rather than personal treasures.

Title page of Tentoonstelling der Nagelaten Werken van Vincent van Gogh.

The works owned by the Vincent van Gogh Foundation are now preserved for public display in the Van Gogh Museum, originally opened in 1973. Russell Shorto’s recent article, “The Woman Who Made van Gogh” (New York Times, April 18, 2021) revealed the gradual uncovering of the extent of Johanna van Gogh’s role in the establishment of the artistic legacy of Vincent van Gogh. In 2009, scholars who were working on the multi-volume publication of the Van Gogh letters were finally granted access to Jo’s diaries, which the family had kept private since her death. More recently, some of her own reflections on her remarkable life can now be read in an English translation of the diaries, accessible online: https://www.bongerdiaries.org.

Published on April 30, 2021

Written by: Nicola J. Shilliam, Western Art History Bibliographer, Marquand Library of Art and Archaeology

Media Contact: Barbara Valenza, Director of Library Communications

Newsletter

Subscribe to Princeton University Library’s e-newsletter for the latest updates on teaching and research support, collections, resources, and services.