Nova Cæsarea: A Cartographic Record of the Garden State, 1666-1888

Perspective: Surveying Land

Direction (compass angle) and distance are the essential elements of a field survey. How to accurately measure them and map them has been the domain of surveying since people began to own land. The geometry and mathematics (trigonometry) of triangles have played a central role.

The Colonial Surveyor

Robert Erskine (1735–1780), Scottish-born inventor and engineer, and ironmaster of New Jersey's Ringwood Ironworks during the Revolutionary War, was appointed as the first Geographer and Surveyor General of the Continental Army by George Washington on July 27, 1777. 1 In his reply from Ringwood, dated August 1, 1777, Erskine outlined the duties and difficulties he envisaged in such work:

Your favour of the 28th Ult: concerning the Office of Geographer, I had the honour to receive yesterday at Pompton. The distinction you confer on me, I beg leave to acknowledge with gratitude; and shall be happy to render every service in my power, to your Excellency, and to the Cause in which the rights of humanity are so deeply interested: on these accounts it is necessary to be explicit; both by laying before you my Ideas of the whole subject at once; and likewise by setting forth, how much time and attention I can immediately bestow on the proposed department.

It is then perhaps proper to begin with a general View of the nature of the Business; in order to shew, what may really be accomplished by a Geographer; that more may not be expected, than it is practicable to perform; and, that an estimate may be made of the number of assistants required should the Map of any particular district be required in a given time. It is obvious, that in planning a Country, great part of the ground must be walked over, particularly the banks of Rivers and Roads: as much of which may be traced and laid down in three hours, as could be walked over in one; or in other words, a Surveyor who can walk 15 miles a day, may plan 5 miles; if the Country is open, and Stations of Considerable length can be obtained, then perhaps greater dispatch may be made: very little more, however, in general can be expected; if it is Considered, that the Surveyor, besides attending to the Course and measuring the distance of the way he is traversing, should at all convenient places where he can see around him, take observations and angles to Mountains, hills, steeples, houses and other objects which present themselves, in order to fix their site; to Correct his work; and to facilitate its being Connected with other Surveys. A Surveyor might go to work with two Chain-bearers and himself; but in this case, he must carry his own Instrument, and some of them must frequently traverse the ground three times over at least: therefore, to prevent this inconvenience and delay, as men enough can be had from Camp without additional expence, six attendants to each Surveyor will be proper; to wit, two Chain-bearers, one to Carry the Instrument, and three to hold Flag staffs; two flags, indeed, are only wanted in Common; but three are necessary for running a straight-Line with dispatch; and the third Flag may be usefully employed in several cases besides. From what one Surveyor can do, it will therefore appear, that in making a plan, like all other businesses, the more hands are employed in it, the sooner it may be accomplished; likewise, that the director of the Surveyors, will have full employment in making general Observations, and Connecting the different Surveys as they come in, upon one general Map; and, at any rate, that a Correct Plan must be a work of time.

A great deal however may be done towards the formation of an useful Map, by having some general outlines justly laid down; and the situation of some remarkable places accurately ascertained; from such Data, other places may be pointed out, by information and computed distances; in such a manner, as to give a tollerable Idea of the Country; especially with the assistance of all the maps in being, which can be procured: & this, perhaps, is as much as can be expected, should plans be required to keep pace with the transitions of War.

Navigable Rivers, and those which cannot be easily forded, and likewise the Capital Roads, should be laid down with all the accuracy possible; but, in the Map of a Country, the general course of fordable Rivers need only be attended to; it not being practicable to express small windings but on a large Scale, and the same accuracy not being required here, which is necessary to ascertain the quantity and boundaries of private property: in general, therefore, the adjacence to, and intersection of such Rivers with roads, will determine their Course with sufficient exactness: the situation of woods and Mountains too, may be remarked in a similar manner.

Young Gentlemen, of Mathematical genius, who are acquainted with the principles of Geometry, and who have a taste for drawing, would be the most proper assistants for a Geographer such in a few days practice may be made expert Surveyors. The Instrument best adapted for accuracy and dispatch, is the Plain-Table; by this, the Surveyor Plans as he proceeds; and not having his work to protract in the evening, may attend the longer to it in the day. One of these Instruments, with a Chain and ten Iron-Shod arrows, should be procured for each of the Surveyors it may be thought proper to employ—but I ought not to trouble your Excellency with the Minutice of the business; it is time now to proceed to my own situation... 2

Early Surveying Guides

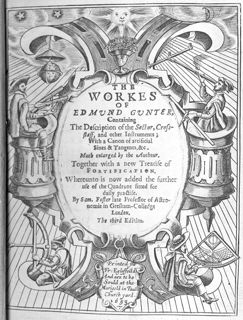

Edmund Gunter (1581–1626). The Workes of Edmund Gunter, Containing the Description of the Sector, Cross-staff, and Other Instruments; with a Canon of Artificial Sines & Tangent, &c. Much Enlarged by the Author. Together with a New Treatise of Fortification. Whereunto Is Now Added the Further Use of the Quadrant Fitted for Daily Practice. By Sam. Foster Late Professor of Astronomie in Gresham-Colledge London (London: Fr. Egleffeild, 1653) [Historic Maps Collection]. First edition of Gunter's collected works.

One of the great instrument-makers of the seventeenth century, English mathematician Edmund Gunter introduced a one hundred–link surveying chain in 1620, which became a standard surveyor's tool well into the nineteenth century (see an example below). He is also considered to be one of the inventors of the logarithm, and was the first to use the terms cosine, cotangent, and cosecant for the complements to an arc of the sine, tangent, and secant.

John Love (active 1688). The Whole Art of Surveying and Measuring of Land Made Easie. Shewing, by Plain and Practical Rules, How to Survey, Protract, Cast Up, Reduce or Divide Any Piece of Land Whatsoever; with New Tables for the Ease of the Surveyor in Reducing the Measures of Land. Moreover, a More Easie and Sure Way of Surveying by the Chain, Than Has Hitherto Been Taught. As Also, How to Lay Out New Lands in America, or Elsewhere; to Make a Perfect Map of a River's Mouth or Harbour; with Several Other Things Never Yet Published in Our Language (London: W. Taylor, 1716) [Rare Books Division]. The third edition, with additions.

[I]f you ask, why I write a book of this nature, since we have so many very good ones already in our own Language? I answer, because I cannot find in those Books, many things, of great consequence, to be understood by the Surveyor. I have seen Young men, in America, often nonplus'd so, that their Books would not help them forward, particularly in Carolina, about Laying out Lands, when a certain quantity of Acres has been given to be laid out five or six times as broad as long. This I know is to be laught at by a Mathematician; yet to such as have no more of this Learning, than to know how to Measure a Field, it seems a difficult Question: And to what Book already Printed of Surveying shall they repair to, to be resolved? [from Love's preface].

He published the first edition in 1688, simplifying the process with clear rules and procedures. There are chapters on geometrical definitions and problems, instruments and their uses, diverse ways to take the plot of lands, how to calculate acreage, how to lay out, reduce, and divide plots of land, and trigonometry. Instructions are given in using Gunter's chain and measuring angles with the circumferentor, plane table, and semicircle. The text is illustrated with numerous examples and, in this edition, includes "A Table of Sines and Tangents to Every Fifth Minute of the Quadrant." Later editions of the book appeared for more than a century; the twelfth (1793) and thirteenth (1796) editions were published in New York. The work changed little over the years, even considering the later revisions of Samuel Clark.

Surveying Instruments

Measuring angles

![Thomas Greenough (1710–1785). Surveyor's compass or circumferentor, ca. 1760 [Historic Maps Collection].](https://libimages.princeton.edu/loris2/exhibits%2Fnj-historic-maps%2Fintro%2Fsurveyors-compass-1760.jp2/full/!320,320/0/default.jpg)

![Thomas Greenough (1710–1785). Surveyor's compass or circumferentor, ca. 1760 [Historic Maps Collection]. Diameter (including frame), 6.25 inches; between the sights, 12 inches; height, 6 inches. Cherrywood stand and frame support. The paper compass card shows a man in a red coat looking out to sea with a quadrant instrument, and a sailing vessel rides on the horizon. The card has eight points, like a star (one is a fleur-de-lis), and bears printed divisions of 0° to 90° in each of its four quadrants. The inscription reads, "Made by Thomas Greenough, Boston, New England." Greenough was an American colonial instrument maker.](https://libimages.princeton.edu/loris2/exhibits%2Fnj-historic-maps%2Fintro%2Fsurveyor-compass-detail.jp2/full/!750,750/0/default.jpg)

By sighting two different points from the same spot, such as the corner of a property, a surveyor could easily determine the intervening horizontal angle by addition or subtraction of the two recorded compass readings.

The surveyor's compass was superseded by the theodolite.

Measuring distance

![Unknown maker. Gunter's chain, pre-1800 [Historic Maps Collection]. Handmade wrought iron handles, rings, and links; pewter tallies (these are usually brass), 65.7 feet in length. Ideally, 1 link = 7.92 inches; 100 links = 4 rods = 66 feet; and 80 chains = 5,280 feet or 1 mile. An acre is 10 square chains.](https://libimages.princeton.edu/loris2/exhibits%2Fnj-historic-maps%2Fintro%2Fgunters-chain.jp2/full/!320,320/0/default.jpg)

There are several sorts of Chains... But that which is most in use among Surveyors (as being indeed the best) is Mr. Gunter's... [Love, p. 54].

This is one of the standard distance measurement tools of colonial surveyors, lasting well into the nineteenth century. Theoretically, each link should measure 7.92 inches, but in this heavily used example the blacksmith varied the number of connecting rings between the links from one to four to make up for the variations in link length. Divisions along the chain are noted by the claw-shaped tallies (one to four toes), with notches indicating the number of ten-link sections; a round tally indicates the halfway point. (This chain is missing the second four-toe tally.) The total distance from handle end to handle end is approximately sixty-six feet.

In the field, the chain is stretched out by chain bearers along a specific path (or compass bearing), until the surveyor confirms it is straight and true to the line being followed; then the chain is anchored to the ground with steel arrows or pins. The measurement is recorded, and, keeping the last end still secured, the process is repeated again and again until the endpoint is reached.

Chains were superseded by steel tapes.

![Unknown maker. Waywiser or surveyor's wheel, ca. 1850 [Historic Maps Collection]. Constructed almost entirely of oak and pine wood including the gear train that drives the dials that indicate the distance traveled. The wheel rim and the dial arrows are metal. There are two boxes mounted on the frame: one opens to reveal the gear train; the other provides storage space and includes a small drawer. In addition, a larger storage box hangs below the frame. The two rear supports are folded up when pushing the waywiser (those are modern replacements). (Photographs courtesy of Luke Vavra.)](https://libimages.princeton.edu/loris2/exhibits%2Fnj-historic-maps%2Fintro%2Fwaywiser2.jp2/full/!750,750/0/default.jpg)

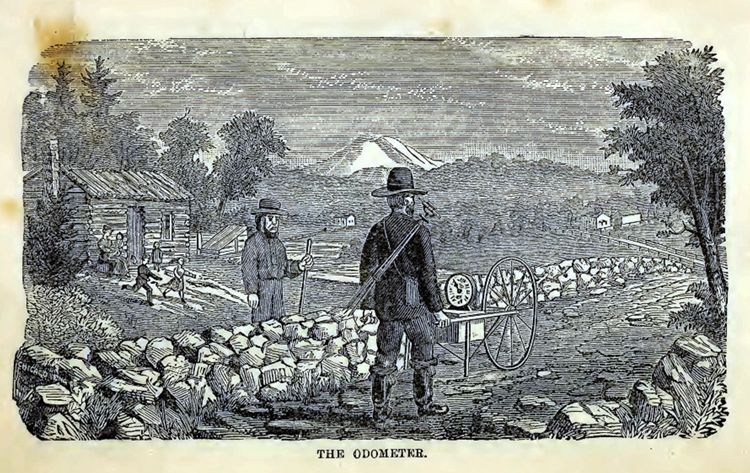

With this wheelbarrow-like instrument—not much different in function from today's odometer— a surveyor could walk a route over a dirt road or field and easily measure the distance traveled. The revolutions of the large wheel turn dials in the wooden box that provide readings in feet, rods, furlongs, and miles. The circumference of the wheel is 8.25 feet; hence, two revolutions equal one rod (16.5 feet); forty rods make a furlong, and eight furlongs match one mile.

Sample Survey

![Joseph Yard. Survey of James Clarke and David Brearley lots near the Stony Brook, dated December 2, 1749 [Clarke Family of New Jersey Collection, Manuscripts Division]. Manuscript map on paper, 15.5 × 27 cm. Notice that the lengths are given in number of chains and links between posts and trees.](https://libimages.princeton.edu/loris2/exhibits%2Fnj-historic-maps%2Fintro%2F1749-brearley-yard-survey.jp2/full/!750,750/0/default.jpg)

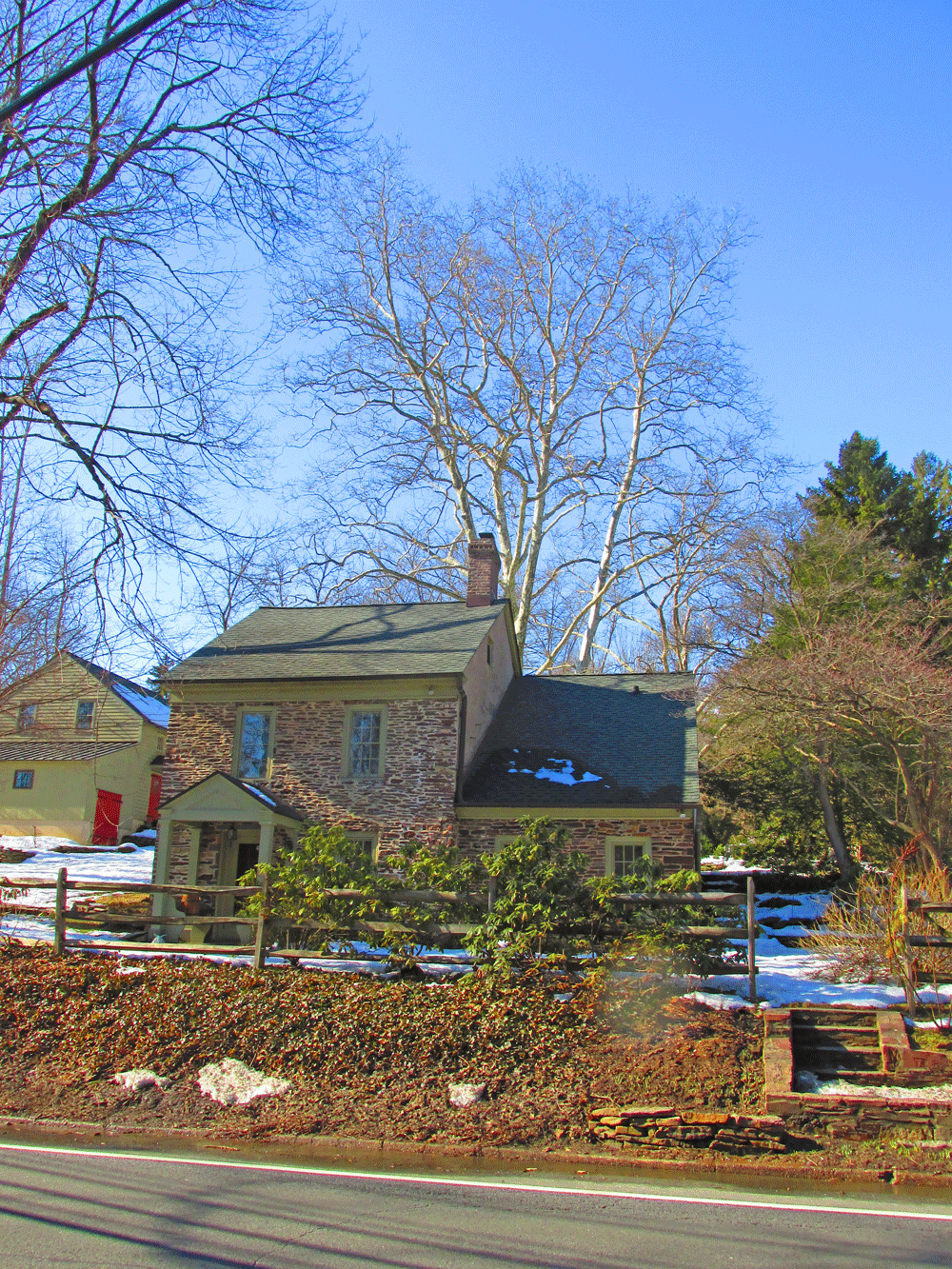

The three lots are located in Princeton Township, on the northwest side of Route 206 (Stockton Street) before it crosses the Stony Brook Bridge from Princeton. (The bend is still in the road.) The Brearley house on the map is now 487 Stockton Street.4 David Brearley (d. 1785), Clarke's brother-in-law, was the father of David Brearley (1745-1790, usually spelled Brearly), signer of the Constitution and chief justice of the New Jersey Supreme Court.

![Unknown maker. Waywiser or surveyor's wheel, ca. 1850 [Historic Maps Collection].](https://libimages.princeton.edu/loris2/exhibits%2Fnj-historic-maps%2Fintro%2Fwaywise1.jp2/full/!320,320/0/default.jpg)